23 May 2023 • 6 minute read

Supreme Court’s Warhol decision clarifies limits of copyright fair use

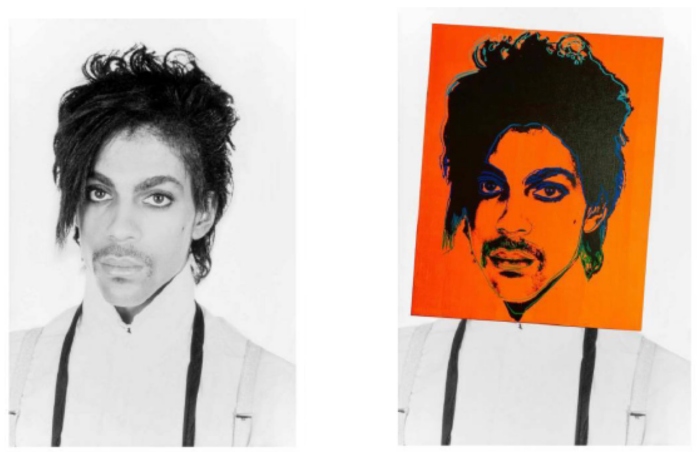

The US Supreme Court has issued a major decision on copyright fair use in Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al., 598 U.S.__ (2023). The 7-2 majority opinion, written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor and released on May 18, 2023, handed a decisive victory to the copyright owner Lynn Goldsmith in her dispute with the Andy Warhol Foundation over the use of her original photograph of the artist Prince.

The decision was jurisprudentially narrow, focusing on one factor in a four-factor balancing test in the context of a particular challenged use. Yet the decision is nonetheless of great practical significance, as it both narrowed the copyright fair use defense and rejected proposals to expand this defense considerably.

The Court held that the first copyright fair use factor – the “purpose and character” of Warhol’s challenged use, “including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes” – favored copyright owner Goldsmith. Id. Slip Op. at 2. In doing so, the Court confirmed the objective nature of the purpose inquiry, emphasized the importance of commerciality in the fair use analysis, and rejected calls to weigh the first factor in favor of the challenged use whenever the original is used to convey a "new meaning or message.”

Photo originally licensed on a one-time basis

In 1984, Goldsmith licensed to Vanity Fair use of her copyrighted Prince photo on a one-time basis. Vanity Fair hired artist Andy Warhol, who created a silkscreen of that photo for publication. Warhol also created additional works using Goldsmith’s photo. The Andy Warhol Foundation later licensed one of those additional works to Condé Nast to illustrate a magazine story about Prince. Goldsmith sued for copyright infringement based on the Foundation’s unauthorized licensing activity. The Southern District of New York granted Warhol summary judgment on copyright fair use; the Second Circuit reversed.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari and affirmed the Second Circuit’s ruling that the first fair use factor did not favor Warhol. Clarifying and applying its landmark 1994 ruling in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569 (1994), the Court gave three reasons for this conclusion.

First, Goldsmith and Warhol shared substantially the same purpose for their respective Prince works, to wit, licensing a Prince image to a magazine for a story about the musician. Second, the use was commercial, a statutory consideration that many federal courts had recently discounted in finding “transformative” use under the first factor. Third, Warhol failed to otherwise persuasively justify its unauthorized use. Because the Foundation had argued only the first fair use factor on appeal, the Second Circuit’s overall judgment of no fair use was upheld.

Ruling bolsters copyright owners’ ability to enforce their rights

While the Court’s ruling ostensibly just reaffirms precedent, it explains that precedent in a way that bolsters copyright owners’ ability to enforce their rights against an increasingly common form of copying. This form of copying does not “target” the original through parody or other forms of commentary or criticism. Rather, it “flavors” the original with new expression or aesthetics to convey a message that bears on something other than the original work itself. Warhol itself is an example of this type of “transformation,” where the secondary use lacks commentary on the original work. Since Campbell, courts had become more willing to find such uses to be fair, even when they were overtly commercial and borrowed heavily from the originals. The Ninth Circuit’s 2020 decision in Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. ComicMix, LLC, 983 F.3d 443 which rejected an argument that the “mashing-up” of Star Trek and Dr. Seuss’s works was a transformative fair use, was an important counterweight to this trend. But the Supreme Court had not weighed in on the copyright fair use defense for artistic works since Campbell.

Now, the Supreme Court’s decision in Warhol not only arrests this post-Campbell trend toward a more expansive concept of “transformative” use, but also swings the pendulum at least somewhat in the other direction. Future copyright plaintiffs facing such arguments can now rely on the Court’s holding that while “[c]opying might have been helpful to convey a new meaning or message” and “often is,” that “does not suffice under the first factor.” Warhol, Slip op. at 35.

The Court also likened Warhol’s copying and alterations to the Prince photo as indistinguishable “from a long list of would-be fair users: a musician who finds it helpful to sample another artist’s song to make his own, a playwright who finds it helpful to adapt a novel, or a filmmaker who would prefer to create a sequel or spinoff, to name just a few.” Id. This language is a logical corollary to Campbell’s teachings that where the alleged infringer “merely uses [the original] to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another's work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger.” 510 U.S. at 580.

Derivative rights and commerciality

The Court’s discussion of the copyright holder’s “derivative” rights (part of the bundle of copyright reserved for the copyright owner) will also impact future fair use cases. The Court explained the “intractable problem” with Warhol’s argument that any use that adds some new expression, meaning, or message supports the first fair use factor. Such an interpretation of 17 U.S.C. § 107(1), the Court explained, cannot be reconciled with the copyright owner’s derivative rights. “Otherwise, ‘transformative use’ would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works” as “[m]any derivative works, including musical arrangements, film and stage adaptions, sequels, spinoffs, and others that ‘recast, transfor[m] or adap[t]’ the original, 17 U.S.C. §101, add new expression, meaning or message, or provide new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.” The Court also reaffirmed the importance of whether a use is “commercial” in the first-factor analysis, while maintaining that commerciality is not alone dispositive.

Overall, Warhol provides greater clarity to the first fair use factor, reaffirming the need to evaluate “purpose” objectively and to carefully consider whether the claimed fair use would impair the copyright owner’s derivative right. Whereas the Court had expressly limited last year’s Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc. decision to its underlying technological context – a position confirmed by Warhol, Slip op. 20 n.8 – Warhol will apply to a wide variety of copyright claims, such as music, art media, and the inevitable AI-related claims that will work their way through the federal courts.

Find out more about this decision and its impact on your business by contacting the authors or your usual DLA Piper attorney.