11 July 2025 • 16 minute read

Deep Sea Mining Uncovered: Part One

Digging into the Deep Blue Sea: The Basics of Deep Sea MiningKey takeaways

- Deep Sea Mining (DSM) involves extracting mineral deposits from the seabed (at depths below 200 metres). The deep seabed covers approximately two-thirds of the total seafloor and is rich in deposits of critical minerals required in battery manufacturing such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, and zinc.

- Proponents of DSM argue for its potential to accelerate the net-zero transition through supplementing the world’s battery mineral supplies with marine mineral resources. On 24 April 2025, the United States White House issued an Executive Order expediting a domestic process to authorise the exploitation of resources in areas beyond its national jurisdiction (international waters) under its domestic Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act.

- Opponents of DSM highlight its potential to cause irreversible disturbance and destruction to habitats and organisms, which may also accelerate global warming. 37 States so far have taken positions against DSM in international waters, some calling for a moratorium, others a precautionary pause, and one a ban.

- While small-scale exploratory devices have been deployed to test machinery for DSM, no commercial mining has yet been undertaken.

Introduction

With news of renewed interest emerging in recent weeks following the United States White House’s Executive Order (Unleashing America's Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources), deep sea mining (DSM) is the subject of both excitement and controversy. Its proponents argue that DSM may be the key to unlocking billions of tonnes of critical battery minerals. Its opponents argue that DSM will cause irreversible damage to the environment. What is clear is that the world – and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) – must strike a balance between protecting unique and ecologically important species in the deep sea and meeting the mineral demand necessary for the transition to net-zero.

This article, Part One in our three-part series, uncovers the basics of DSM – what is it, where the potential mineral deposits are located, who are the key DSM players, the state of play of current DSM technology, and the science for and against DSM.

In Part Two, we will outline the regulatory and legal framework applicable to DSM, with Part Three exploring the geo-politics, the wider international law issues at play and the landscape of international and domestic disputes likely to arise in relation to DSM.

The treasures of the deep sea

The deep seabed covers approximately two-thirds of the total seafloor and is rich in deposits of critical minerals required in battery manufacturing such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, and zinc. These minerals are used in rechargeable batteries that are needed for renewable energy storage, such as for electric vehicle batteries. These mineral deposits come in three forms: polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides, and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. DSM involves extracting these mineral deposits from the seabed at depths below 200 metres.

Of significant interest to DSM proponents and opponents alike is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), which spans 4.5 million square kilometres in the Pacific Ocean. A conservative estimate is that 21.1 billion dry tonnes of polymetallic nodules exist in the CCZ manganese nodule field, the largest in area and tonnage of the known global nodule fields.1 Based on that estimate, the tonnages of many critical metals in the CCZ nodules are greater than those found in global terrestrial reserves. About 7.5 billion dry tonnes of cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts are estimated to occur in the Prime Crust Zone, the area with the highest tonnage of critical-metal-rich crust deposits. So far, 19 of the 31 exploration contracts the ISA has issued are for the exploration for polymetallic nodules in the CCZ.

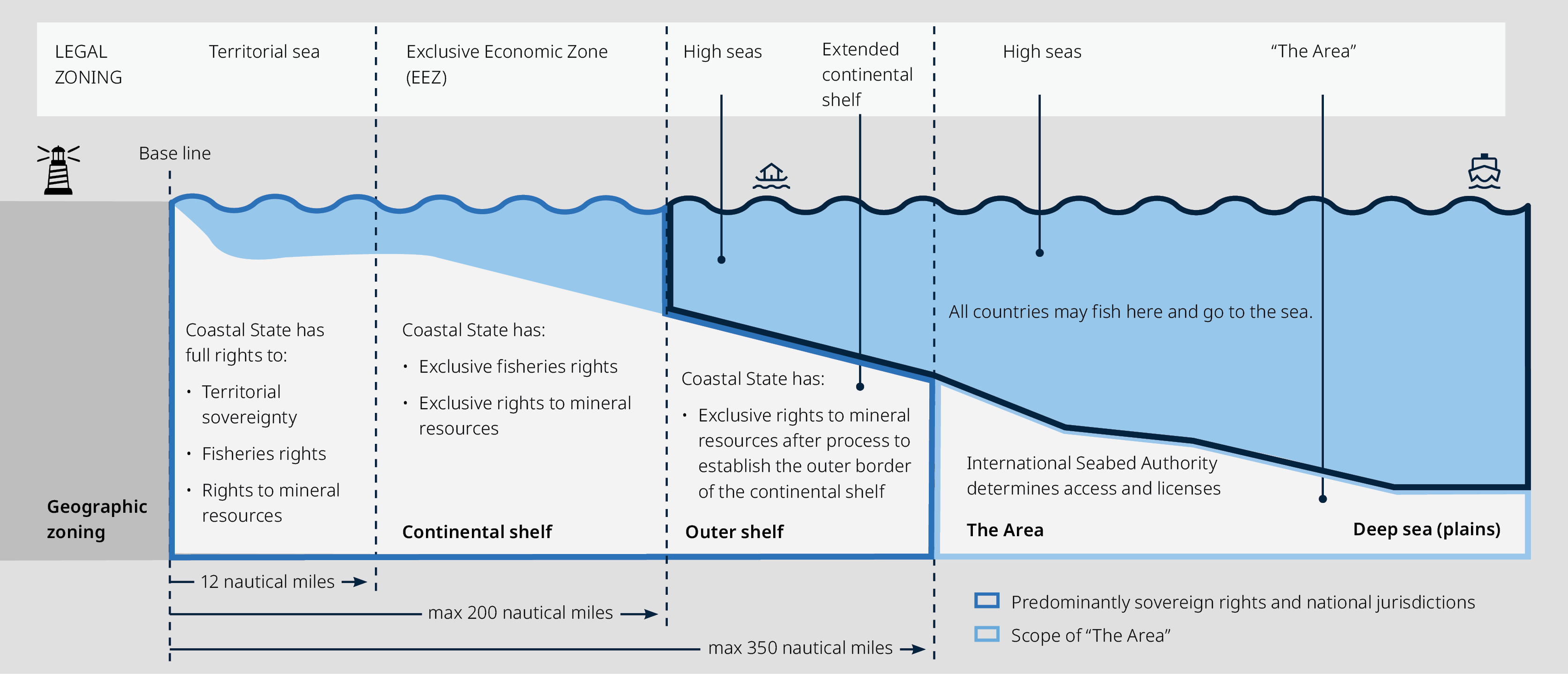

Importantly, much of the CCZ sits in international waters, beyond national jurisdictions. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) refers to the seabed, ocean floor, and subsoil beyond limits of national jurisdiction as “the Area”.

A State’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends from the baseline of its territorial sea out to 200 nautical miles from its coast. In that EEZ, a State has rights to explore, exploit, conserve, and manage the natural resources of the waters and of the seabed. As such, a State has the means to permit and regulate DSM within its EEZ without the ISA’s approval, but in line with its obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment.2 The Area, in contrast, is subject to the ISA’s administration. UNCLOS provides that the Area must be protected from harmful effects and any benefits derived from it must be equitably shared among all State Parties.

States such as Norway and the Cook Islands moved swiftly towards DSM in their own EEZs. In January 2024, Norway became the first State to announce the opening of an area of 281,000 square kilometres in its EEZ to commercial DSM exploration.3 However, in November 2024, Norway paused DSM exploration in its EEZ, after it was blocked by the country’s Socialist Left Party. Norway's Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Stoer, described the pause as “postponement” and said preparatory work on regulations and environmental impact would continue.4

Most recently, talks between China and the Cook Islands regarding research efforts have accelerated.5 Korea, China, and India have all also sponsored, or contracted exploration contracts through the ISA in the CCZ.6 In the private sphere, industrial metals start-up The Metals Company (TMC) leads the charge on DSM. TMC has been granted three exploration contracts through its subsidiaries in the CCZ, sponsored by Nauru, Kiribati, and Tonga.

The treasure hunt – technology and proposed process

The technology to be used in DSM is largely untested and the expected processes for mining and processing are in the experimentation phase. There will, however, be a difference in process between the types of deposits.

Nodules

The expected process for DSM of nodules is to transport tractor-sized machines down to the seabed, which would then crawl along the bottom, collecting the nodules and sending them back to the surface via long tubes as they go (almost like “vacuuming” the sea floor). How these machines would collect the nodules is one of the issues still being researched, although most likely the machines would “hoover” the nodules up from the seabed. Given the risks of disturbing and collecting sediment, and neighbouring life forms, alternative methods such as using a special rake to sieve the nodules out are also being explored.

Crust and sulphides

Polymetallic sulphides can be mined around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. The specific process for mining crust and sulphides is, to date, unconfirmed and under-developed, though likely to follow a very similar form to current terrestrial mining.

Crust mining is technologically more difficult than nodule mining. Unlike nodules, which sit on a sediment substrate, crusts are attached to substrate rock, meaning they cannot simply be picked up from the seafloor like nodules. The crust must be separated from the substrate rock before they can be collected. It is anticipated that crust mining operations may include fragmentation, crushing, lifting, pick-up, and separation.7 A general method of crust recovery might consist of a bottom-crawling vehicle attached to a surface ship by means of a hydraulic pipe lift system and electrical cord. The vehicle might use articulated cutters that would allow crusts to be fragmented while minimising the amount of substrate rock collected. The technology to be used in this process is unconfirmed and there have been no field tests of equipment capable of mining cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts.

The unknown: Evidence against DSM

While small-scale exploratory devices have been deployed to test machinery, no commercial mining has yet been undertaken. As such, there is no clarity on the actual impact DSM may have on the marine environment and whether those impacts will be irreversible. In this instance, the general approach is to adopt the precautionary principle.8 There are those who suggest that DSM will likely cause long-term environmental, economic, and social harms.9 However, the competing argument is that DSM will be a more economically and environmentally responsible alternative to ongoing reliance on terrestrial mining operations for sourcing the battery minerals necessary for the transition to net-zero.10

In a joint publication of Environment America, U.S. PIRG Education Fund, and Frontier Group, ‘We don’t need deep-sea mining’, the authors suggests that DSM is not necessary to meet the global critical minerals demand, analyse the expected environmental impacts, and argue that many of the resources needed for the net-zero transition would already be accessible if we were to utilise a circular economy.11 Ultimately, the publication recommends a moratorium on DSM in the Area.

Further, it is argued that DSM will be highly energy intensive and is likely to produce a high level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, depending on the mining and transport procedure undertaken. However, it is hard to gauge the actual emissions impact without any exploitation activities being commenced to date. There has been very little scientific attention on the potential terrestrial impacts of DSM, including GHG emissions. Scientific studies, investigating the hypothesis that metal production from manganese nodules is less GHG emission-intensive compared to conventional sources, are scarce. The proposed metallurgical processing of nodules is currently similar to that of land ores. Consequently, the severity of climate impact is less dependent on whether ores come from the deep sea or land and is more dependent on the properties of processing: mainly the sources of fuel and electricity used, process efficiency, and processing technique.12

Alongside the minerals 200 to 6,500 metres below the surface, is an estimated 8,000+ undiscovered marine species (including the so-called “gummy squirrel”, a species of sea cucumber discovered in 2018 and gaining instantaneous fame when John Oliver covered DSM in "Last Week Tonight"). Exploration to date suggests that only 0.01 percent of the total area of the CCZ has been sampled by scientists, that 85 percent of the global seabed remains unmapped, and that 90 percent of species discovered are new to science. A recent publication in the Science Advances Journal noted that “sixty-five percent of all in situ visual seafloor observations [from the authors’ dataset, being the “largest deep submergence dataset yet compiled”] were within 200 nm of only three countries: the United States, Japan, and New Zealand [and that] ninety-seven percent of all dives [the authors] compiled have been conducted by just five countries: the United States, Japan, New Zealand, France, and Germany”.13 The authors therefore considered that “the small and biased sample is problematic when attempting to characterize, understand, and manage a global ocean”.14

Even decades after experimental dredging disturbed a site, scientific monitoring confirms that very few ecosystems recover. As such, it is argued that DSM threatens the existence of thousands of species on the sea floor. Some ecological and biodiversity concerns include:

- the direct loss of unique and ecologically important species and populations as a result of the degradation, destruction, or elimination of seafloor habitat, many before they have been discovered and understood;

- the production of large, persistent sediment plumes that would affect seafloor and midwater species and ecosystems well beyond the actual mining sites;

- the interruption of important ecological processes connecting midwater and benthic ecosystems;

- the resuspension and release of sediment, metals, and toxins into the water column, both from mining the seafloor and the discharge of mining wastewater from ships, detrimental to marine life including the potential for contamination of commercially important species of food fish such as tunas;

- noise pollution arising from industrial machine activity on the ocean floor and the transport of ore slurries in pipes to the sea surface, that could cause physiological and behavioural stress to marine mammals and other marine species;

- light pollution from mining activities introducing bright lights into an environment that, but for the biochemical emission of light from living organisms such as glow-worms and deep sea fish, is otherwise constantly dark. This could have significant impacts on species that have adapted to these dark conditions which may be blinded by the introduction of lights from deep sea mining operations; and

- uncertain impacts on carbon sequestration dynamics and deep-ocean carbon storage.

As recently as late June 2025, a new study in the Frontiers in Marine Science Journal also noted that areas targeted for Deep Sea Mining by TMC in the CCZ, contained the presence of one sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) which is listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.15

The opportunity: Evidence for DSM