13 January 2026

A deep dive into RMA reform – what is changing?

Overview

On 9 December 2025, the New Zealand Government released the Natural Environment Bill and the Planning Bill. These Bills are intended to repeal and replace the Resource Management Act 1991 by mid-2026.

Together, the Bills are designed to provide distinct, but consistent, approaches to environmental management and land-use planning in New Zealand.

Public submissions are being called for both Bills. The closing date for submissions is 4.30 pm on Friday 13 February 2026.

This article covers key aspects of the Bills, including:

- Foundational provisions and the Environment Court

- National direction and plans

- Consenting

- Designations

- Compliance and enforcement

Overview

The foundational provisions of the Bills introduce new guiding purposes and principles for the resource management regime. The Bills also provide direction on the consideration of effects, and establish a new framework for setting environmental limits and managing natural resources within those limits.

How will the foundational provisions be dealt with under these Bills?

Part 2 of both Bills has been expanded, rather than only containing purpose and principles (as under the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA)). Part 2 of the Bills, titled “Foundations”, contains:

- goals

- procedural principles

- direction regarding the consideration of effects

- restrictions on land use (previously sections 9–15C of the RMA)

- environmental limits (in the Natural Environment Bill)

Goals

The two Bills identify specific goals (set out in clause 11 of both Bills). The goals aim to narrow the scope of the environment and planning systems, while providing clearer direction for decision-making.

There is some overlap between the goals in the Bills, including managing the risks of natural hazards, providing for Māori interests through iwi participation in the development of planning instruments, and the development and protection of identified Māori land.

The Planning Bill goals address topics such as:

- separating incompatible land uses

- supporting economic development

- creating urban and rural functionality

- providing for infrastructure

- maintaining public access to water bodies

- protecting areas of high natural character, outstanding natural features, and sites of significant historic heritage from inappropriate use and development

The Natural Environment Bill goals focus more on:

- environmental protection

- human health

- use of natural resources within environmental limits

- biodiversity conservation

Procedural principles

Both Bills identify the same procedural principles (clause 13). The principles aim to:

- balance cost and feasibility with the scale and significance of projects

- ensure documents are in plain English and understandable to the general public

- avoid unnecessary repetition between frameworks

Te Tiriti o Waitangi / Treaty of Waitangi

The RMA requires decision-makers to “take into account” the principles of the Treaty. This has enabled the courts to interpret the RMA in a way that attempts to protect Māori interests, and to require good-faith engagement and consultation.

The Bills propose to remove the reference to Treaty principles and instead set out specific clauses through which the Crown’s responsibilities in relation to Te Tiriti o Waitangi / the Treaty of Waitangi are recognised.

The Planning Bill sets out five areas where those responsibilities would apply:

- giving effect to the Māori interests goal in clause 11

- consultation with iwi authorities before notification of a proposed national instrument

- specific consultation duties when preparing regional spatial plans

- when preparing land-use plans, requiring authorities to have regard to statutory acknowledgements, prepare and change land-use plans in accordance with specific legislation, and undertake consultation (including having regard to advice provided)

- imposing duties on decision-makers in relation to designations on identified Māori land

The Natural Environment Bill sets out three areas where those responsibilities would apply:

- giving effect to the Māori interests goal in clause 11

- consultation with iwi authorities before notification of a proposed national instrument

- when preparing natural environment plans, requiring regional councils to have regard to:

- statutory acknowledgements

- preparing and changing plans in accordance with specific legislation

- undertaking consultation (including having regard to advice provided)

Environmental limits

The Natural Environment Bill provides for the setting of environmental limits for:

- air

- freshwater

- coastal water

- land and soil

- indigenous biodiversity

The limits are intended to protect human health and the life-supporting capacity of the natural environment.

Setting environmental limits

Human health limits must be set by the responsible Minister in national standards. Ecosystem health limits must be set by regional councils in natural environment plans. To set or change ecosystem health limits, the council must follow the plan change process.

Environmental limits must be expressed as either:

- a biophysical state for a management unit; or

- the amount of harm or stress to the natural environment permitted in a management unit.

The Bill sets out decision-making criteria for setting environmental limits. The decision-maker must consider:

- the extent, scale, and impacts of any environmental degradation

- the trend, direction, and pace of degradation

- the difficulty of reversing degradation if action is delayed

The Bill contains explicit direction that a lack of scientific certainty is no reason to delay a decision needed to prevent significant or irreversible harm to the natural environment.

When Ministers and regional councils set environmental limits, they must consider the existing capacity of the natural environment to withstand or recover from pressures and disturbances, and the impact of the proposed limit. Assessing that impact requires consideration of factors such as:

- effects on the life-supporting capacity of the natural environment or human health

- community needs or aspirations for the economy, society, and the natural environment

- the magnitude and spatial extent of any over-allocation of natural resources

- alternative ways of providing for natural resource use that are consistent with protecting or enhancing the natural environment (including alternative locations)

Tools for managing natural resources

The proposed methods for managing natural resources within environmental limits are:

- caps on resource use; and

- action plans.

Caps on resource use are preferred, unless a regional council determines they would not be effective.

A cap on resource use describes the maximum amount of resource use that can occur without breaching an environmental limit. It informs the allocation of resource use in plan rules and permits. A cap can be expressed as:

- a land use (for example, the extent of an activity);

- an input (for example, the amount of fertiliser that may be applied); or

- an output (for example, the volume or rate of contaminant discharge, such as an annual nitrogen discharge cap).

Action plans may provide guidance for:

- decision-making on applications for natural resource permits

- reviewing permit conditions

- preparing rules in a natural environment plan and/or caps on resource use

Breaching environmental limits

A regional council must avoid breaching an environmental limit. If there is sufficient evidence that an environmental limit will be breached in the medium to long term, the council must evaluate the likelihood of breach. If breach is likely, the regional council must take action to avoid it, including by:

- preparing an action plan

- changing its natural environment plan or cap on resource use

- reviewing conditions (specified in the plan) applying to natural resource permits and making necessary adjustments

- changing the way natural resources are allocated; or

- establishing a safety margin.

If an environmental limit is breached, the regional council must publicly notify the breach and its cause. The regional council must then prepare an action plan setting out how it will manage natural resource use to remedy the breach and review the cap on resource use.

Effects

Both Bills provide guidance on the consideration of effects.

The Planning Bill includes effects that decision-makers must disregard, including (notably):

- the internal and external layout of buildings on a site (for example, provision of private open space)

- the demand for, or financial viability of, a project (with some exceptions)

- the visual amenity of a use, development, or building in relation to its character, appearance, aesthetic qualities, or other physical feature

- the social and economic status of future residents of a new development

- views from private property

- effects on landscape

- the effect of setting a precedent

However, the clause is explicit that it does not restrict the management of:

- areas of high natural character within the coastal environment, wetlands, lakes, rivers, and their margins

- outstanding natural landscapes and features

- sites of significant historic heritage

- sites of significance to Māori

- effects of natural hazards

Both Bills also formalise an effects management hierarchy by directing that the decision-maker must consider how adverse effects are to be: avoided; minimised; or remedied “where practicable”; or offset or compensated “where appropriate”.

The Natural Environment Bill directs decision-makers to consider the positive effects of enabling activities, the effects on natural resources, the effects of natural hazards, and any other effect (except those excluded by the Planning Bill).

What issue is the reform looking to solve with foundational provisions?

The Government intends the reform to:

- speed up the delivery of infrastructure (for example, by narrowing the scope of effects subject to assessment and regulation)

- provide more direction to decision-makers (for example, through procedural principles)

- provide a greater role for central government in shaping and overseeing the new system (for example, through Ministerial functions and powers)

- reduce time and cost (including by requiring decision-makers to take all practicable steps to achieve procedural principles)

- safeguard the natural environment and human health through the environmental limits framework

What outstanding questions or issues are there with the foundational provisions?

It is likely to take some time for the foundational provisions to come before the courts. Until then, there may be uncertainty as to how competing goals will be balanced (for example, safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air, water, soil, and ecosystems, while enabling the use and development of natural resources).

We also expect a teething period for regional councils setting environmental limits, especially where there may be limited data available on a specific natural resource.

It is a goal of the reform to provide more central government control and direction. Given this, ultimately the greatest uncertainty is the content of the national direction to come.

What do regulators need to know about the foundational provisions?

Key points for councils include:

- Effects on character, heritage and amenity are to be disregarded: The Planning Bill does not restrict the management of “sites of significant historic heritage”. However, effects on the visual amenity of a use, development, or building in relation to its character, appearance, aesthetic qualities, or other physical feature, are to be disregarded by decision-makers.

- Setting ecosystem health limits: The process for setting ecosystem health limits may be specified in national standards, otherwise councils can follow its own methodology.

- New tools to manage natural resources: Caps on resource use and action plans will be used to manage air, water, land, and soil, and indigenous biodiversity within environmental limits

- Māori interests: A shift from “taking into account” Treaty principles to a directive clause specifying how the Crown’s responsibilities under Te Tiriti o Waitangi / the Treaty of Waitangi are recognised.

- More efficient procedures: Balancing costs and feasibility with scale and significance, while ensuring information is succinct, non-repetitive, and in plain language.

- Achieving goals: Regulators must “seek to achieve” the goals set out in the Bills when exercising functions, duties and powers.

What do applicants need to know about the foundational provisions?

Key points for applicants include:

- Reduced scope of effects: The scope of effects which can be considered under the Bills is narrowed, which may mean the resource consent application process is less expensive and time consuming for applicants.

- New goals: Decision-makers must seek to achieve new goals, including supporting and enabling economic growth and providing for infrastructure to meet current and expected demand.

- Positive effects of enabling activities: Decision-makers are directed to consider the positive effects of enabling activities.

What is changing with the Environment Court?

Schedule 9 of the Planning Bill sets out provisions applying to the Environment Court and its proceedings under both Bills. The Environment Court will continue to have the same powers, duties and discretions in respect of consents, declarations and enforcement. It will also hear appeals on designations and merits appeals on bespoke provisions in land-use plans.

The ability for the Environment Court to consider direct referrals and nationally significant proposals is removed. Its role in plan making will become more limited, and a Planning Tribunal will be established as a division of the Environment Court.

The Planning Tribunal will have power to review decisions made under the Planning Bill (for procedural and legal error, whether the decision was reasonable in the circumstances, and notification decisions). It will also be able to exercise declaratory powers under the Planning Bill and the Natural Environment Bill, and any other powers provided for by any other Act.

Overview

Together, the Bills would significantly reduce the number of plans and higher order documents produced nationwide to simplify the system compared to the current system.

“National instruments” would form a top-down funnel approach to national direction. The top of the funnel would be a National Policy Direction (NPD), supported by national standards that provide more detailed direction for implementing the NPD.

How will national direction and plans be dealt with under these Bills?

The Bills would work together to create a system intended to form clear goals, which are then funnelled down into more targeted and specific plans. Each level of the funnel must give effect to the instrument directly above it (or higher, if directed). At each level, fewer matters should be “up for debate” or able to be re-litigated.

Community engagement is intended to occur during development of the combined regional plan rather than at the consenting or permitting stage. However, opportunities for public participation at these earlier stages appear to be reduced.

National instruments

National instruments would sit at the top of the planning hierarchy. They are proposed to be a suite of secondary legislation intended to create nationally consistent approaches and standardised plan content.

The first national instrument would comprise short, targeted NPDs. NPDs would particularise the goals and outcomes the planning and environmental management systems seek to achieve, providing direction on national priorities to inform each planning document below. The NPD would also direct how the goals will be achieved and resolve conflicts of goals between both Bills. NPDs must give direction on matters of policy and may state objectives, policies or directives that apply to key instruments and may direct activity classification and notification requirements.

Once made, national standards would be produced to implement the NPD. National standards are intended to:

- provide procedural or administrative consistency

- provide regulatory consistency

- provide specific direction on how a goal is achieved where not covered by an NPD

National standards would include environmental limits and nationally standardised zones and overlays for land use and natural resource management.

The Minister would set each national instrument and must have regard to principles such as achieving compatibility between NPD goals (rather than achieving one goal at the expense of another). Not all goals need to be achieved at the same time, and conflicts between national instruments should be resolved as reasonably practicable. Regional and district councils must give effect to each national instrument through the Regional Combined Plan.

Combined plans

Each region would make a single combined plan that gives effect to the NPD and national standards. The combined plan would comprise three components:

- a regional spatial plan;

- a natural environment plan under the Natural Environment Bill; and

- a land-use plan under the Planning Bill.

Regional spatial plans would sit under national standards in the hierarchy. They would set the strategic direction for development and public investment priorities over at least 30 years, implement national instruments to support urban development and infrastructure provision within environmental limits, and support a co-ordinated approach to infrastructure funding and investment by central government, local authorities, and other infrastructure providers.

Draft regional spatial plans would be developed by new spatial plan committees. Their terms of reference would be set by one or more local authorities, who must agree matters such as key geographical areas, issues and opportunities. The plans must be developed in compliance with national instruments, in the manner specified in those instruments. The spatial plan committees would prepare an options assessment report, consult on the draft plan, and recommend the draft plan to all local authorities in the region for approval to publicly notify it (Schedule 2 of the Planning Bill currently outlines these matters).

Land-use plans under the Planning Bill (replacing district and city plans under the RMA) would be prepared by territorial authorities to implement the relevant spatial plan by applying nationally standardised zones, rules and methodologies. Territorial authorities must use standardised provisions or where allowed by national instruments, create bespoke provisions supported by a justification report explaining why a departure from the national approach is necessary.

Natural environment plans under the Natural Environment Bill (replacing regional plans under the RMA) would regulate the use, protection and enhancement of natural resources within a region and assist regional councils to carry out their functions and responsibilities under the Bill.

Regulatory relief provisions

A new feature in both Bills is a requirement for councils to provide a framework for, and to give, “regulatory relief” if rules relating to specified topics have a “significant impact” on the reasonable use of land.

“Specified topics” include: significant historic heritage sites or structures; outstanding natural landscapes or outstanding natural features; sites of significance to Māori; and areas of high natural character in the coastal environment, wetlands, lakes, rivers, or their margins.

Regulatory relief may include:

- monetary payment

- waiving or reducing rates or fees

- granting additional development rights elsewhere on the property or another site owned by the landowner

- access to targeted grant programmes

However, what amounts to a “significant impact” is yet to be determined.

Submissions and notification

The scope for who can submit on proposed plans notified for public submissions has been narrowed under both Bills. The following persons will be allowed to make submissions to a local authority on a proposed plan notified for public submissions:

- A "qualifying resident" of the territorial authority’s district or the regional council’s region;

- A person who has an interest in the proposed plan greater than the general public;

- A nearby local authority; or

- The local authority itself.

The following persons will be allowed to make further submissions to local authorities on proposed plans notified for public submissions:

- A "qualifying resident" of the territorial authority’s district or the regional council’s region;

- A nearby local authority; or

- The local authority itself.

To be a qualifying resident in a region or district, submitters must be ratepayers, an infrastructure provider, a natural person whose main place of residence in within the region / district or a business that has an office or operates from the region / district.

Both Bills also provide for targeted notification in relation to consents and permits. Where an application for a permit or consent is the subject of a targeted notification, only a person served with notice of the application may make a submission. Targeted notification is able to be used in circumstances where certain groups are affected, such as customary rights groups or if the local authority determines the effects on certain groups are more than minor (i.e. more than a noticeable, perceivable adverse effect on a person or resource of a scale that effects can be accepted or mitigated).

Transition

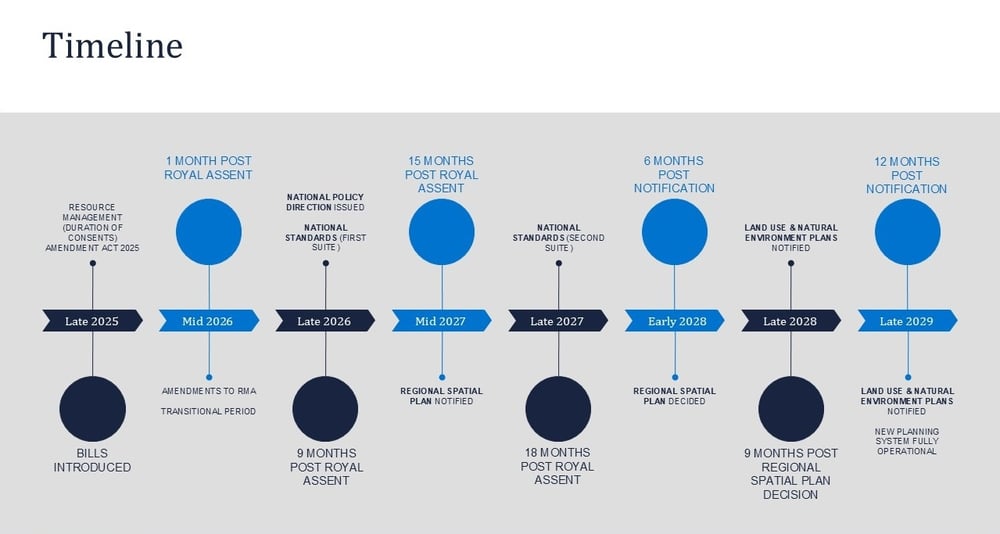

National instruments will be delivered in two main stages as the first key instruments to be developed:

- The first suite of national instruments to inform spatial plans by the end of 2026, including one NPD for each Bill and environmental limits relating to human health for freshwater, coastal water, land, soil and air domains, national standards required for the spatial plan; and

- The second suite to be delivered in mid-2027 to include national standards needed for the land-use and natural environmental plan, standardised plan content (Planning Bill land-use zones and overlays) and processes to set and manage ecosystem health limits to safeguard life-supporting capacity.

The combined regional plans will follow, with spatial plans set to be notified in late-2027 and remaining plans prepared and notified in late-2028.

What issue is the reform looking to solve with national direction and plans?

The Bills seek to standardise plan provisions to enable faster planning than under the RMA, reduce costs, and make the system easier to navigate for applicants with projects in multiple regions.

Councils would be required to use standardised provisions and zones unless they include bespoke provisions which depart from the standardised provisions. Bespoke provisions can only be included in plans where their use is authorised by a national instrument or national instruments do not preclude the inclusion of bespoke provisions. The use of any bespoke provisions will need to be justified, including in terms of an assessment of costs and benefits at a level of detail that corresponds to the scale and significance of the proposed content.

A more stringent plan process will also apply where bespoke provisions are used. Where a national instrument allows territorial authorities to include bespoke planning provisions, these provisions will subject to merits submissions and appeals. Nationally standardised provisions will not require submissions or be subject to merit appeals as they will be required by national instruments.

What outstanding questions or issues are there with national direction and plans?

Central Government would have a more active role in both shaping and overseeing the new system than under the RMA. Much will therefore depend on how NPDs and other national instruments are drafted and implemented by instruments lower in the hierarchy. In relation to bespoke provisions, it remains unclear what criteria authorities will use to justify departures from nationally standardised provisions. The proposed regulatory relief provisions may also discourage the use of bespoke provisions.

What do regulators and applicants need to know about national direction and plans?

Councils would continue to have statutory functions in the new planning system. Councils will:

- Jointly make and maintain a spatial plan for the region;

- Regional councils will make and maintain a natural environment plan for their region;

- Territorial authorities will make and maintain a land-use plan for their city/district;

- Unitary authorities will make and maintain both a natural environment plan and a land-use plan; and

- Administer and implement their regulatory plans, including consenting and permitting, monitoring and compliance under its plans and regulating and managing effects.

The reforms are intended to reduce costs for local government. Although, councils will still be implementing plans, consenting and monitoring compliance, standardisation of planning provisions, zones and less notification requirements and submissions received during the process are intended to reduce costs and the time taken to produce plans.

Councils will no longer be able to provide for the following matters in their plans:

- Internal and external layout of sites

- Visual amenity

- Views from private property

- Landscape effects

- The effect of setting a precedent

With these matters expressly out of the planning scope, less flexibility for bespoke plan provisions and the aim of reducing the need for consents, more activities are likely to be able to be undertaken without needing to apply for consents. Where consents are required, the aim is that the process is more efficient and cost-effective for applicants.

The Bills simplify activity classification and alter participation in the consenting and permitting process by raising the threshold for notification. The intention is faster, cheaper and more certain consenting and permitting, while reducing the overall number of consents and permits required.

The Planning Bill establishes a new Planning Tribunal (as a division of the Environment Court), intended to provide fast dispute resolution for certain disputes between system users and councils.

How will consenting and permitting be dealt with under these Bills, and what role does the Planning Tribunal have?

There is no fundamental change, at least at a high -level of generality, to how the proposed new system approaches consenting. However, there are a range of differences to the current RMA approach, which cumulatively are intended to enable faster, cheaper and more certain consenting and permitting, while reducing the overall number of consents and permits required.

Planning consents are required under the Planning Bill and fit into two broad categories. These are landuse consents and subdivision consents. The relevant territorial authority is the consent authority. This framework is similar to the district consenting framework under the RMA.

In contrast, natural resource permits are required under the Natural Environment Bill and fit into four broad categories. These are coastal permits, discharge permits, landuse permits and water permits. The relevant regional council is the permit authority. This framework is similar to the regional consenting framework under the RMA.

Like the RMA, the Bills continue to provide for activity classification, but only provide for permitted, restricted discretionary, discretionary, and prohibited activities (ie, controlled and non-complying activities are gone). The Bills set out "principles for classifying activities", which broadly align with existing best practice in terms of activity classification. For example, the principles provide that an activity should be classified as permitted if the activity is acceptable or a specific assessment of the activity is not required, whereas an activity should be classified as a prohibited activity if it will have an unacceptably high level of adverse effects that cannot be managed by consent conditions.

The Bills also provide a framework for the processing of consent / permit applications that is similar to the RMA. Consent processing time frames are provided for. The Bills empower consent / permit authorities to request further information / reports and provide for consequences where an applicant fails to respond.

Public and what is now termed "targeted" notification are provided for, but the effects thresholds have been raised, and “special circumstances” is no longer a relevant consideration. Public notification will occur when the adverse effects are more than minor or significant (depending on the Bill) and there are no affected persons or not all affected persons are able to be identified. In contrast, targeted notification will occur when the adverse effects are more than minor and all affected persons can be identified.

The Bills also adopt a familiar approach to considering applications and decision-making, with some key differences. These include that there are certain effects, outside the scope of the Bills, that must not be considered. Those effects are numerous, and include visual amenity (character and appearance), certain effects on landscape, and precedent effects. Another difference is that decision-makers must not consider a “less than minor adverse effect” and this concept is specifically defined. There is also no equivalent to decision-making on applications being “subject to Part 2” of the RMA, however a goal or goals may be relevant to decision-making in some situations. Another key difference is that what is commonly referred to as the permitted baseline is now mandatory rather than discretionary. Notably, a permit must not be granted if granting it would result in the breach of an environmental limit (unless the breach is authorised by a standard). More extensive provisions address the relevance of an applicant’s compliance history to decision-making on applications.

Conditions may still be imposed, and the Bills introduce a new procedure relating to providing applicants (and any submitters) with any draft conditions and an opportunity to comment. A consent / permit authority must take comments into account, but only to the extent they cover technical or minor matters.

The Bills continue to provide for commencement and duration of consents / permits (including lapse) and provide for the circumstances in which consent / permit conditions can be reviewed.

The Planning Bill provides for limited direct appeal rights to the Environment Court on consents in addition to a new review procedure in the Planning Tribunal. Appeals in relation to permits are to the Environment Court.

The suite of provisions relating to the Planning Tribunal are set out in Schedule 10 of the Planning Bill. The Planning Tribunal is established as a division of the Environment Court. The specific roles of a chairperson and adjudicators are provided for, with prescribed functions.

The Planning Tribunal’s jurisdiction is limited but reasonably wide-ranging. It is empowered to review certain decisions of a local authority for procedural and legal error, can consider whether the decision was reasonable in the circumstances, and will also have declaratory powers. The matters within the review jurisdiction are circumscribed, and include the review of notification decisions. They also include reviewing the reasons for an application not being progressed in accordance with a relevant statutory timeframe. The matters within the declaratory jurisdiction are also circumscribed and include the proper interpretation of the conditions of a consent / permit. The Planning Tribunal is also empowered to review decisions granting regulatory relief.

Procedures of the Planning Tribunal are to be prescribed by regulations or directed in a practice note, and more broadly, the Planning Tribunal is required to regulate its own procedure in a way that best promotes the timely and efficient resolution of matters within its jurisdiction. There is an express presumption that the Planning Tribunal will make a decision on the basis of the same evidentiary and legal considerations that were before the local authority, and that a hearing is not required. Hearings may however be ordered, and legal representation may be permitted. Costs may be awarded in by the Planning Tribunal, but in limited circumstances.

Planning Tribunal decisions can be appealed to the Environment Court, but only on a point of law. An exception is made for review of notification decisions, which can be appealed to the High Court, but again only on a point of law. There is no further right of appeal against the Environment Court’s decision on an appeal against a decision of the Planning Tribunal. The right to apply for judicial review is preserved, but only after the right to appeal to the Environment Court has been exercised.

What issue is the reform looking to solve with consenting and permitting?

At a high-level, the changes to consenting / permitting discussed above are intended to enable faster, cheaper and more certain consenting and permitting, while reducing the overall number of consents and permits required.

Similarly, establishing the Planning Tribunal is intended to provide for a faster, and more cost-effective, way of resolving certain, lower-level, disputes between system users and councils.

What outstanding questions or issues are there with consenting and permitting?

On the whole, the new consenting / permitting processes is largely familiar. Inevitably there will be refinements through the legislative process that are aimed at improving the system and ironing out any bugs.

Some key questions that will require more meaningful engagement from submitters on the Bills in the context consents / permits and the Planning Tribunal include:

- Has the right balance been struck in terms what effects are out of scope, particularly when effects are interrelated and dynamic?

- Is the definition of a "less than minor adverse effect" appropriate, noting the inability for these effects to be considered?

- Has the right balance been struck in terms of providing for activity classification?

- Are the effects thresholds for notification appropriate and has the right balance been struck in terms of constraints on public participation?

- Is the Planning Tribunal’s jurisdiction appropriately limited, and will it be able to deliver faster and more cost-effective dispute resolution?

- Is the limited appeal right in relation to decisions of the Planning Tribunal appropriate in the context of its jurisdiction?

What do regulators and applicants need to know about consenting and permitting?

There is no fundamental change, at least at a high-level of generality, to how the proposed new system approaches consenting. But consenting and permitting will occur within a new framework that is informed by the overall system architecture and goals, which is different (as explained above).

Having said that, the detail is important, and the workability of the proposed new consenting and permitting system needs to be interrogated carefully by regulators and applicants alike.

A fundamental question for many will be whether the appropriate balance is struck to ensure that the system delivers on the promise of efficiency while also ensuring appropriate development is enabled at the same time as protecting what is important.

Some of the issues that the Planning Tribunal is required to consider and resolve may be complex, and there could be considerable demands placed on its processes once it is established and the new consenting and permitting processes commence.

Overview

The Planning Bill is set to make some significant changes to designations as we currently know them under the RMA, albeit the fundamentals appear to remain the same. The broad process will be similar to that found under the RMA - a ‘designating authority’ (cf. requiring authority) will be able to obtain a designation through the ‘spatial planning process’ (cf. plan change process) or ‘an improved, less onerous version of the current process’. However, the detail of those processes appears to have departed from the status quo and there is now an avenue to provide for strategic long-term planning of infrastructure through the regional spatial planning process.

How will designations be dealt with under these Bills?

Designating authorities would be able to obtain a designation through the spatial planning process and ‘an improved, less onerous version of the current process’ under the RMA. However, before examining changes made to substance, it is useful to first look at the changes made to terminology.

Changes to terminology

The term ‘requiring authority’ is to be replaced with the term ‘designating authority’. A designating authority at first blush appears to reflect what is currently considered a ‘requiring authority’ under the RMA with the addition of a ‘person that operates infrastructure’ approved by the Minister.

A ‘network utility operator’ approved by the Minister becomes a ‘core infrastructure operator’ approved by the Minister, with the definitions under the RMA and Planning Bill remaining largely the same with the addition of Health New Zealand in respect of health facilities. For completeness, it is proposed that requiring authorities under the RMA will continue as designating authorities (subject to certain Orders still being in place).

Instead of ‘outline plans’ under the RMA, the Planning Bill proposes ‘construction project plans’. This appears to build on the process for outline plans under the RMA by clarifying the purpose of construction project plans and providing for greater detail to be included.

The “improved, less onerous version of the current process”

A designating authority still provides notice to a territorial authority for designation. The Planning Bill sets out there is no duty under it to consult about a proposed designation (subject to other statutory requirements to consult), albeit the Bill then sets out when to give full or ‘targeted’ (cf. limited) notification. When assessing effects for the purposes of full notification, the assessment is relative to the ‘built environment’. A hearing commissioner may then be appointed to be a ‘recommending authority’ (and in certain circumstances must be appointed) and a hearing conducted if required. If no commissioner is appointed, the recommending authority is the territorial authority.

The recommending authority then recommends the designation be confirmed (either with or without modifications or conditions) or withdrawn. When making its recommendation, it must ‘have regard to … the strategic need for the project in the location proposed’. Significantly, this does not require an assessment of any alternative sites, routes, or methods, nor whether the designation is better provided in any alternative location. Additionally, there is no requirement to have regard to strategic need where ‘the relevant spatial plan identifies the project in a location consistent with the location of the designation footprint’ or the designating authority has sufficient interest in the underlying land to undertake the project. The ability to disregard strategic need in the former circumstance presumably reflects that strategic need will be considered through the spatial planning process.

In terms of effects, a recommending authority is required to have regard to positive effects and significant adverse effects on the built environment. They are only to have regard to adverse effects generally where either:

- the recommending authority considers that effect cannot be appropriately managed through a construction project plan; or

- the designating authority is seeking to incorporate the details of a construction project plan into the designation.

The designating authority then has 30 working days to accept (either in whole or part) or reject the recommendation, and the territorial authority provides a notice of that decision.

Submitters and relevant territorial authorities (except where the territorial authority is the designating authority) have a right of appeal to the Environment Court. The Environment Court determines the appeal ‘as if it were the recommending authority’. After the designating authority has accepted the recommendation, and any appeals are resolved, the territorial authority must incorporate the designation into their land use plan.

There is also the option to incorporate the proposed designation into a proposed plan where a territorial authority intends to notify a proposed landuse plan for public submissions no later than 40 working days after receiving the notice. If the designating authority consents, the notice is considered through the proposed landuse plan process.

The spatial planning process

Designations could also be provided for in the spatial planning process. When preparing a draft regional spatial plan, a spatial planning committee must invite a designating authority to apply. The designating authority can either secure a designation through the spatial planning process or simply request the spatial plan ‘have indicative locations for any future designations identified in the draft regional spatial plan’. The latter simply requires a designating authority to provide an assessment of strategic need for the future designation.

If a designating authority requests a designation be included through the spatial planning process, the spatial planning committee must decide whether to accept the application. If accepted, the designating authority then prepares a notice as if providing notice in the ordinary way (outlined above) and the notice is included in the draft regional spatial plan as part of the spatial planning process. The independent hearings panel considering the draft spatial plan then makes a recommendation, which the designating authority can accept or reject. There remains an ability to appeal the designating authority’s decision to the Environment Court. The designation is then incorporated into the regional spatial plan and the relevant landuse plan.

Effect of a designation and other mechanics

The effect of a designation under the Planning Bill appears to be much the same as what is currently provided for under the RMA, with the addition of allowing contravention of ‘national rules’ where the rules expressly allow it.

A designation would continue to prevent a person from doing something ‘that would prevent or hinder the project to which the designation relates’. The Planning Bill provides a process whereby a person may apply to the designating authority to do something that would prevent or hinder a designation, and there is a right of objection to the Planning Tribunal if the designating authority refuses.

The Planning Bill retains the system of priority for competing designations from the RMA. Where two or more designations overlap, the designating authority that holds the earlier designation may exercise their designation without seeking approval from the competing designating authority, while the designating authority that holds later designation must seek approval.

Finally, the ability for the Environment Court to order the designating authority responsible for the designation or proposed designation to acquire or lease all or part of the owner’s estate or interest in the land under the Public Works Act 1981 is retained. This provides a landowner with the ability to force the designating authority to acquire the land or interest in the land where ‘designation or proposed designation prevents reasonable use of the owner’s estate or interest in the land’.

Overview

The Bills propose a significant shift in how compliance and enforcement would be managed. The new system aims to address compliance and enforcement more consistently, with centralised oversight intended to support consistent and effective enforcement across Aotearoa New Zealand.

How will compliance and enforcement be dealt with under these Bills?

Compliance and enforcement under the new Bills shift towards deterrence, introduces new tools and widens the scope of enforcement tools available to regulators. By introducing compliance history checks, requiring financial assurances, reinforcing the polluter pays principle, and increasing penalties, the system shifts toward a more robust and consistent approach. These measures are designed to prevent environmental harm, ensure remediation where damage occurs, and create stronger incentives for responsible behaviour across all regulated activities.

New tools of note include:

- Monetary benefit orders to cover commercial gain from committing an offence.

- Adverse publicity orders requiring offenders to publicise non-compliance, impacts, and penalties.

- Enforceable undertakings allowing a person to respond to alleged non-compliance without admitting guilt. These may include paying compensation to another person and/or the regulator, or taking action to avoid, minimise or remedy actual or likely adverse effects arising from contravention.

- Pecuniary penalty orders payable to the Crown or another person if the Court is satisfied the person has contravened, or permitted a contravention of, the Act, regulations, or a national rule.

What outstanding questions or issues are there with compliance and enforcement?

The Government is considering whether to establish a national compliance and enforcement regulator through a separate legislative process to administer compliance and enforcement functions under the new system. This is not proposed in this reform, but if progressed, its functions could include:

- Monitoring and enforcing compliance with environmental rules.

- Standardising approaches to compliance and enforcement across Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Responding to complaints about non-compliance.

Watch this space as to whether a new regulator is created.

In terms of the new compliance and enforcement tools, it remains to be seen how the processes will work in practice, including how councils would use them. It is also unclear what offending would be considered most suitable for the new tools, whether councils will update enforcement manuals to reflect the changes, and how early prosecutions under the new regime would be handled.

What issue is the reform of compliance and enforcement looking to solve?

The reform aims to address long-standing concerns that penalties for RMA offending have effectively operated as a licence to offend, with consequences that do not sufficiently deter breaches.

The reform seeks to modernise the RMA approach, arguably aligning more closely with frameworks such as the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (which includes, for example, restrictions relating to insurance). The reform also reflects a shift towards more permitted activities, which in turn places greater emphasis on compliance, monitoring and enforcement. To support this, it introduces a wider range of tools to strengthen how breaches are addressed.

At the same time, the reform seeks to tackle weaknesses in the current system, where responsibility for compliance is spread across many councils, each with differing approaches, levels of resourcing and frequency of enforcement. By introducing central oversight and standardised processes, the reform aims to create greater certainty and consistency for users of the system.

What do regulators and system users need to know about compliance and enforcement?

Key points for regulators:

- Monitoring and compliance: Territorial authorities would be responsible for monitoring compliance and undertaking enforcement relating to administering and implementing the regulatory plan of their district.

- Financial assurance requirements: Territorial authorities would be enabled to set charges to fund their responsibilities.

- Strategy: Territorial authorities must prepare and publish a compliance and enforcement strategy in the prescribed manner.

- New tools: Regional councils and territorial authorities should consider how to use the new tools to achieve positive enforcement outcomes.

We recommend that regulators begin considering how these new tools can be incorporated into their enforcement programmes. Taking the time to understand the changes now will make it easier to utilise them effectively once the reforms are in place. We are available to discuss this further.

Key points for system users:

- Polluter pays principle: Stronger compliance and enforcement mean those responsible for environmental offending must meet prevention and remediation costs, and if prosecuted will face high potential fines.

- Consequences are tougher: As implemented by the Resource Management (Consenting and Other System Changes) Amendment Act 2025, maximum penalties for offending are significant (NZD1 million or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 18 months for individuals and NZD10 million for companies) and defendants can no longer rely on insurance to pay these increased fines.

- Compliance history matters: Regulators can consider an applicant’s compliance record when assessing permits or consents, with poor performance serving as grounds for refusal.

- Up-front costs may apply: System users may be required to provide financial security.

There is now greater risk associated with any form of environmental offending. The consequences are more serious, and regulators have a wider range of tools at their disposal. Anyone carrying out activities that interact with the new Acts will need to be particularly careful with their processes. We are available to discuss these changes further.