30 August 2022

Demystifying SAFEs: The good, the bad, and the ugly

If you have spent any amount of time within the startup ecosystem in the past half decade, you’re likely familiar with the concept of the Simple Agreement for Future Equity, or SAFE. First introduced by YCombinator in 2013, the SAFE has caught on as a quick and efficient way of raising early capital. However, despite being labelled as “simple” (it’s right there in the name!), SAFEs can quite often be confusing to the uninitiated.

This article seeks to lay bare the good, the bad, and the ugly of the SAFE by providing the context necessary to better understand its purpose and underlying mechanisms. Note that this article was updated to take into account some changes in the SAFE landscape since first writing.1 After many years of supporting investors and entrepreneurs alike, we’ve also pulled some of our responses to the most frequently asked questions on SAFEs into a companion article.

History

When originally introduced by YCombinator, the goal of the SAFE was to simplify the process of investing in an early stage startup via a seed financing, in advance of the company undertaking a Series A venture financing. The seed round was often a bridge to future financing, and the SAFE was seen as a uniform, contractual vehicle to issue shares in that future financing, with a potential benefit to the investor for making their investment early.

The core function of a SAFE is to enable an advance investment in a company to bridge finances until a larger financing round can be completed, at which time the advance investment will convert into shares, with the investor benefiting either from a discount in purchase price or a capped value. Convertible notes already achieved this function; however, they can be complicated, with different investors and institutions having their own preferred forms, and in the case of secured promissory notes, require separate security agreements. As a debt instrument, convertible promissory notes could also conflict with a company’s existing debt obligations.

The SAFE was also introduced at a time when there was some amount of uncertainty around California law related to lender registration and its potential application to convertible notes. It was borne of supposed necessity to streamline the process, as a solution to a specific “problem”, which meant that companies and investors alike were perhaps willing to give up some of the established benefits of a convertible note in favour of the SAFE. Regardless of the jurisdictional specificity of this fix, the SAFE’s popularity has been on the rise ever since.

The good

The best thing that can be said about using a SAFE is that it may simplify the process of raising early stage capital. It does this by providing a single standardized form that is widely accepted and therefore (ideally) not subject to negotiation, aside from a very limited set of variable business terms. This uniformity allows the SAFE to be negotiated and entered into quite quickly, and with relative ease. It can also forestall the need for additional documents, like a shareholders agreement, or other administrative overhead that comes with having shareholders. Particularly important in a bridge financing, this simplified process can drastically reduce the time and costs associated with the financing, leaving more of the investors’ money in the startup’s pockets at the end of the day.

While a SAFE is a short-form investment document, it is best suited for early stage bridge financings. This is because investors are likely to be (a) friends and family, who trust the founders and for whom the founders are (one would hope) likely to be mindful of the investment risks, or (b) sophisticated investors within the field who are well attuned to the risks of early stage investment. In ideal circumstances, these early SAFE investors will gain the benefit of a fully negotiated venture level investment once the startup has grown to a stage where a proper valuation can bear fruit. Using a SAFE certainly helps remove some of the awkwardness that can otherwise come with trying to negotiate a valuation with mom and dad.

Aside from the amount of money the investor is advancing, there are only four (potential) elements of the SAFE that are meant to be customized:

- A valuation cap will set the highest permissible value for the company that can be used when converting the SAFE into shares, which provides a floor for the percentage of the company the investor is buying;

- A discount provides the investor with a direct discount on the price per share that they will convert at, as compared to future equity investors;

- A financing threshold sets a dollar amount for a future financing, providing that any financing over this amount will trigger conversion of the SAFE; and

- A MFN (Most Favoured Nation) clause, which allows an opportunity for the SAFE holder to choose to amend its SAFE to match the terms of any SAFEs issued thereafter with more investor favourable terms.

No other terms should be negotiated or customized in an individual SAFE if you wish to maintain the simple integrity of the SAFE. If a party suggests there are more opportunities for negotiable terms using a SAFE instrument, you may typically surmise that party is mistaken about the function and scope of a SAFE. The only other place for any additional terms with a SAFE investor is a side letter, but as discussed below and in our FAQ Article, we recommend careful consideration before entering into side letters in connection with SAFEs.

The bad

Although many of the key conversion facets of a SAFE can generally be found in a convertible promissory note, the reverse cannot be said. Convertible promissory notes may also include additional protections for investors, such as accruing interest on the principal initially invested, a maturity date upon which the note becomes due and repayable (in cash or conversion), and an ability to have the investment secured and registered against assets of the company. As noted above, these are unavailable in a SAFE.

The lack of these additional protections is part of what makes the SAFE a simpler instrument, but it also means the potential risk for investors is greater. To be fair to the SAFE though, being company-friendly is more of a feature than a bug.

Interestingly, YCombinator updated the mechanics of the SAFE conversion calculations in 2018, publishing this new version as a “Post-Money Valuation” SAFE. The big difference here was that the valuation cap used to calculate the SAFE investment into equity was to include the aggregate value of all convertible securities. Post-Money in this sense is a bit of a misnomer and can lead to confusion, as it is really Post-SAFE Money, but still pre-equity financing money (more on this below). This was a move that made SAFEs more investor friendly, as the floor set by a valuation cap was fixed, and any dilution between issuance of the SAFE (whether through issuance of options, convertible notes or other SAFEs) wouldn’t impact a single SAFE holder’s base position.

YCombinator has also removed the “Valuation Cap and Discount” SAFE from its list of available documents, presumably due at least in part to confusion on how to calculate on conversion (it was the conversion most favourable to investors, not both) or additional unintended dilution for founders. Conversion for these SAFEs is discussed below.

The ugly

The real problem with SAFEs is not so much the document itself, but a general failure by some who use it to actually understand how the SAFE itself works and the SAFE’s impact on dilution. Much of the benefit that can be derived from using a SAFE can be undone by this failure to understand or an attempt to get creative with additional terms.

So what happens? Focusing on the SAFE being quick, simple, and cheap can lead some founders to simply download, fill in the blanks, and run with it, or some form thereof. Of course, this is a potentially dangerous way to deal with any legal document, but there’s something about the SAFE that makes founders feel, well, safe in doing this.

From an investor perspective, it’s important to understand that a SAFE is an early stage, risky investment, in many ways the antithesis of a safe investment.

Remember, SAFEs have no maturity date, so they will sit in a company’s books conceivably forever without any mechanism requiring the company to do anything about them. If there is not a qualified financing, or a sale event, the last vestige for the SAFE investor is a company windup or liquidation, wherein the investor may receive up to their original investment back, and that’s only if (a) the company has enough assets to liquidate, and (b) those assets are not eaten up by secured and even unsecured creditors. In the meantime, SAFE investors do not have any of the rights that shareholders would have, or any strong claim for breach of contract.

Another area of potential ugliness arises in connection with the conversion of the investment into shares. While there are a few different ways that a SAFE can be formulated, many investors (and too many founders) do not understand how the actual conversion mechanics function. That’s fine as long as your SAFE and subsequent financings are being managed by someone who does understand, but if not, there are often disconnects between the investors’ expectations (and sometimes even the founders’ expectations) and the reality of what’s written in the SAFE.

In addition to the general misunderstandings that can occur, some of the common pitfalls when using a SAFE include:

- Providing a discount that is too steep. While there’s no hard and fast rule about how much of a discount you may offer your investors, the typical range tends to be between 10-20%, though 5% and 30% are not unheard of. The danger here is that if you provide too steep of a discount (above 30%), SAFE holders may be over represented on your post equity financing cap table. Your future investors may not be pleased about an early investor receiving such a preferential conversion, depending on the comparative size of the investments and the time between investments. At best, this will be an unwanted discussion point in diligence, but at worst, it may turn away potential future investors.

- Negotiating additional terms. Having discussed the Bad and the Ugly aspects of SAFEs, it’s not surprising that many early stage angel investors may want to negotiate additional terms into their actual SAFE document, such as maturity, other conversion benefits, multiples on a sale or liquidation, or other rights. While a SAFE can certainly function with additional terms, there are a couple of dangers here. The first is further complicating the SAFE and defeating some of the purpose of using the “simple”, short-form agreement in the first place. The second is negotiating different terms for different investors. Mismatched discounts, valuation caps, and other terms can mean that you will have to calculate conversion of the SAFEs differently - this can lead to issues (and therefore added complexity and cost) when it comes time to convert. This also makes confusion more likely, and has resulted in many founders finding themselves with far less equity than anticipated at the end of the day. For investors seeking to negotiate a variety of other terms, we generally recommend considering another investment vehicle to achieve their goals.

- Overuse of side letters. The solution to negotiating additional terms within a SAFE has often been to enter into a side letter agreeing to whatever additional terms the company and investor agree upon in connection with the investment. This is such common practice that a side letter actually forms part of YCombinator’s download package (the form letter provides an investor only with pro-rata rights for further investment within the equity financing in which their SAFE converts, but additional terms are often negotiated under this form of side letter). Other common inclusions are information rights, rights of first refusal, negotiation rights, and requirements for terms to be included in an eventual shareholders’ agreement. This may be appropriate (or required) when a more regulated entity is investing through a SAFE (such as a government funded program), but in instances where such terms are less essential to the deal, side letters stack up and create conflicting administrative overhead. It also leads to a question: if a SAFE is really the right instrument, why do we need so many side letters?

- Representing the SAFE in your cap table. Because the SAFE’s conversion into shares will depend on factors that are unknown at the time it is issued, there’s no absolute way to represent the SAFE in your cap table. If you have used a valuation cap, typically this will be used as the stand-in for estimated conversion, but you do have to remember that the conversion could happen at a lower valuation, thereby increasing the number of SAFE shares. As long as this is all noted clearly in your cap table, future investors will understand it, but you do not want to simply list a block of “Friends and Family” at a set number of shares. Once you get closer to the terms on an equity financing, you’ll want to take a close look at how these SAFEs may convert so you understand dilution at the end of the equity financing.

- Not using a consistent SAFE. As previously noted, over the years YCombinator has updated their SAFE to provide (a) for better clarity in valuation calculations and (b) that valuation caps are based on post-SAFE money calculations, and pre-equity financing money calculations. This helps resolve some of the earlier cap table qualms. As such, you want to ensure that you’re using up to date versions, and that any guidance you’re receiving is also up to date, and not mis-matched to a different version of the SAFE or a SAFE written for a different jurisdiction, as discussed below. Consistency among the SAFEs you’re entering into is also critical. While having multiple SAFE rounds can lead to different Valuation Cap or Discount amounts, it’s consistency of mechanics that is key. It is possible to amend and restate a SAFE with a holder, which is discussed in our FAQ article.

While the SAFE originated with YCombinator, their form is also not the only version out there. As one example, the National Angel Capital Organization in Canada has also published their own version of a Canadianized-SAFE. While their form follows a more recognizable agreement format for Canadian lawyers, and a streamlining of some of the more convoluted mechanics of the YCombinator SAFE, as of publication it still described a pre-SAFE financing calculation, as it was published prior to YCombinator’s move to a Post-Money Valuation Cap. Perhaps even more critically, because it’s not in the same form as the YCombinator SAFE, any investor used to the standard SAFE will need to thoroughly review, which may further negate the “simple” benefits. The same can be said for the KISS (Keep It Simple Security), the LEAF (Lean Equity Alternative Financing), and a myriad of other competing forms. Consistency is key. Investors familiar with using SAFEs expect reliability out of these documents. - Failing to get proper advice. Do not get fooled by the term “simple” - there are still complicated mechanics to work through, so make sure that you get good accounting and legal advice. This includes making sure that the SAFE is customized for your jurisdiction, and that you’re following applicable securities laws! For example, if you are a Canadian company (yes, even a private one), you need to be compliant with Canadian securities laws, not just the US securities laws in the default YCombinator SAFE. In 2021, YCombinator began publishing international versions of the SAFE, to try and address some of the jurisdictional issues that can arise. As of current publication, they have provided versions for Canada, the Cayman Islands, and Singapore, and do provide ample warning to seek local legal advice. However as with all “standard” forms, one size doesn’t fit all and there are aspects of the YCombinator’s Canadian SAFE that we have to fix each and every time one is used.

- YCombinator did replace references to stock (US-favoured term) with shares (Canadian-favoured term), but unfortunately still refer to us as attorneys and fail to take into account certain additional jurisdictionally favourable provisions, such as tax credits (noted below).

- Failing to consider other externalities. One of the easiest pitfalls for a founder to fall into is simply assuming that a SAFE is the only way - or even just a preferred way - to raise early funds. While common, a SAFE should not be used unless it fits within a broader financing strategy. Externalities to be considered will vary, but should include consideration of the actual potential investor pool. Friends and family may be content to receive non-voting shares, or use sign onto a voting trust. Some angel groups may strongly prefer convertible notes. Some non-dilutive funding programs may have specific requirements regarding equity or convertible equity instruments.

As an example, in British Columbia, Canada, qualifying small businesses may apply for funding which provides their investors with a 30% refundable tax credit. However this program expressly excludes any form of debt financing, and portions of the YCombinator SAFE have been deemed “debt-like”, meaning companies wishing to take advantage of the program can either sell equity directly or (gulp) amend the SAFE. - Failing to properly consider dilution. As founders are closing a Series A, the excitement can be quickly drawn out of the room if they haven’t fully considered the impact SAFE conversion will have on dilution at the outset. This may occur when the founders keen on a short term exit have already started counting their potential dollars before understanding the additional dilution they will experience when one or more rounds of SAFE holders make their way onto the cap table in earnest. This is less likely to occur when the negotiation of a Series A round takes SAFE conversion into account right from the term sheet stage.

Examples

SAFEs come in a variety of flavours. Some will have a Valuation Cap, some will have a Discount, and some will have both, giving the investor the benefit of whichever calculation puts them in a better position. There is also a version of the SAFE which has no Valuation Cap or Discount, which would generally only be used by an investor intending to make an advance shortly before participating in a full financing round.

Understanding how the Valuation Cap and Discount work in practice can be best illustrated by working through the math.

Valuation cap

As an example of a Valuation Cap being used for conversion, let’s assume we have a SAFE investment of $500,000, with a Valuation Cap of $5,000,000. In the event of a conversion, the SAFE investor will receive shares at the same value as the equity investor (the investor(s) whose investment triggers the conversion), with the Valuation Cap acting as a safety fence to keep the SAFE investor from converting above that price. The Valuation Cap is currently based on the pre-money value of the equity financing, which means that if the equity financing has a pre-money valuation of $2,000,000, the SAFE investor’s investment is included in that amount, meaning in our example that the SAFE investor would hold 25% of the issued and outstanding shares immediately prior to the investment closing.

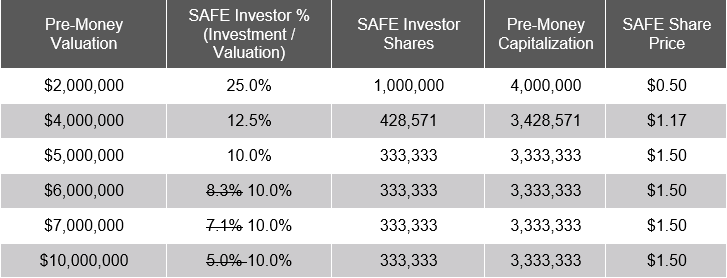

How much the SAFE investor will be diluted depends on the size of investment the equity investor is making, but the Valuation Cap protects the SAFE investor’s position relative to the shareholders prior to the equity financing. If we assume a certain number of shares outstanding immediately prior to the equity investment, the following chart illustrates how the Valuation Cap will play out:

SAFE Investment: $500,000

Valuation Cap: $5,000,000

Shares Outstanding (prior to SAFE conversion): 3,000,000

To add context to the above calculations, let’s walk through that first row. If we have a pre-money valuation of $2,000,000, which includes $500,000 from the SAFE investor, then the SAFE investor holds 25% of the shares prior to the equity investment. To determine how many shares the SAFE investor must be issued (X), we then know that X must be 25% of X + 3,000,000 (the other shares outstanding). That calculation yields 1,000,000 shares, and so the pre-money capitalization is 4,000,000 shares. Calculating the issue price of the SAFE shares is then a simple calculation of the $500,000 SAFE investment divided by the 1,000,000 SAFE shares.

As the above table illustrates, the SAFE investor’s entitlement diminishes as the pre-money valuation increases. The Valuation Cap steps in at the $5,000,000 mark and provides that, despite the equity investor agreeing to a higher pre-money valuation, the SAFE investor will not drop below a certain entitlement (in this example, new issuance of the equivalent of 10% of the then-issued and outstanding shares).

Discount

As an example of a Discount being used for conversion, let’s again assume we have a SAFE investment of $500,000, this time with a discount of 20%. In the event of a conversion, the SAFE investor will receive shares at a value which is 80% of the price paid by the equity investor.

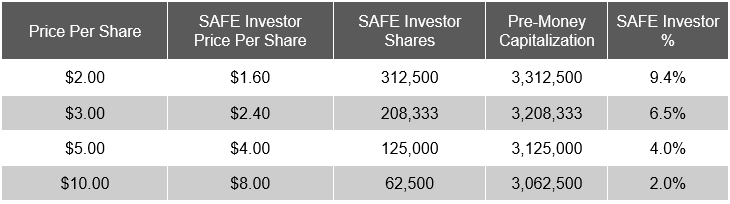

Where a value per share is set in the equity investment, this is an easy enough calculation, such as set out in the below table:

SAFE Investment: $500,000

Discount Rate: 80% (20% discount)

Shares Outstanding (prior to SAFE conversion): 3,000,000

Once again walking through the first row, we start by applying the 20% discount to the $2.00 price per share negotiated in the equity investment, yielding a price per SAFE share of $1.60. If we divide the initial SAFE investment of $500,000 by this price per share, we can determine that 312,500 shares will be issued. That gives us a pre-money capitalization of 3,312,500. The SAFE investor’s percentage can be calculated for reference by dividing the number of SAFE investor shares by the pre-money capitalization, giving us 9.4% prior to the equity investment.

As the above table illustrates, the SAFE investor’s entitlement diminishes as the price increases, as would be expected, but at all times the discount price of the shares is maintained.

If instead of setting a value per share, the equity investment is to be calculated based on a pre-money valuation, you can’t easily use the simple share discount method outlined above. This is because in order to determine a price per share based on a valuation, you must calculate the pre-money valuation divided by the pre-money capitalization, which includes the converted SAFEs, which require a price per share to calculate the number of shares. It’s recursive, and in mathematical terms it is essentially calculating a limit rather than a fixed amount, so again…not exactly simple.

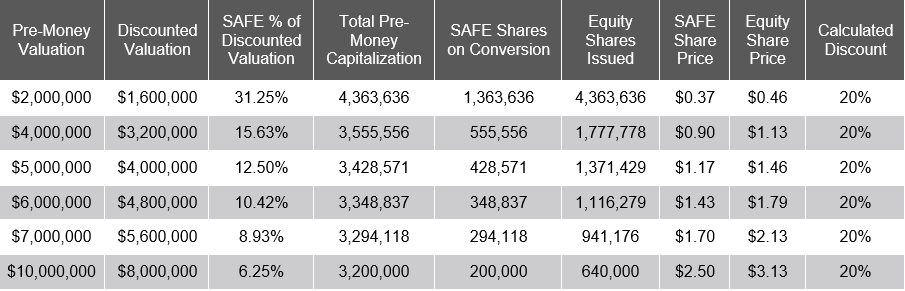

Instead, when using a SAFE with a Discount, and an equity financing using a pre-money valuation to determine value, you will need to calculate the Discount on the pre-money valuation itself. There are more steps involved, but nothing that a good spreadsheet can’t resolve.

Equity Investment Amount: $2,000,000

Looking again at the first row as an example, we first apply the 20% discount to the proposed pre-money valuation of $2,000,000, giving us a discounted valuation of $1,600,000. Based on the SAFE investment of $500,000, that means the SAFE investor holds 31.25% of the shares, prior to the equity investment ($500,000/$1,600,000). Once again, if the number of SAFE shares is X, then X / (X+3,000,000) = 31.25%. This equation yields 1,363,636 SAFE shares, and 4,363,636 total pre-money capitalization.

We can then take the further step of calculating the number of shares to be issued to the equity investor by multiplying the total pre-money capitalization (4,363,636) by the ratio of equity investment amount over pre-money valuation ($2,000,000 / $2,000,000), which results in 4,363,636 shares being issued to the equity investor. The price per share for both the SAFE investor shares and the equity investor shares is found by dividing each party’s investment amount by the number of shares issued to such party, and results in $0.37 and $0.46 respectively.

As the above table illustrates, once again the SAFE investor’s entitlement diminishes as the pre-money valuation increases as we would expect, but by the time we get to calculating the price per share, the discount on the price of the shares is maintained. If we take the difference between those prices ($0.09) and divide it by the equity share price ($0.46), we see that the discount on a per share basis is 20%. We began by discounting the valuation, so this is a confirmation that the method works.

Discount vs. valuation cap

Now we get into the real fun of things: dealing with a SAFE that has both a Discount and a Valuation Cap. The point of providing both is that the SAFE investor will be entitled to convert using whichever mechanism gives them the greatest benefit. Important to note, as of publication YCombinator no longer provides this “either/or” style of SAFE on their website, however as (a) versions of this SAFE still circulate with regularity, (b) are still requested by investors, and (c) they represent the most complicated mechanics in SAFEs, we thought it wise to still provide examples of these SAFEs in action.

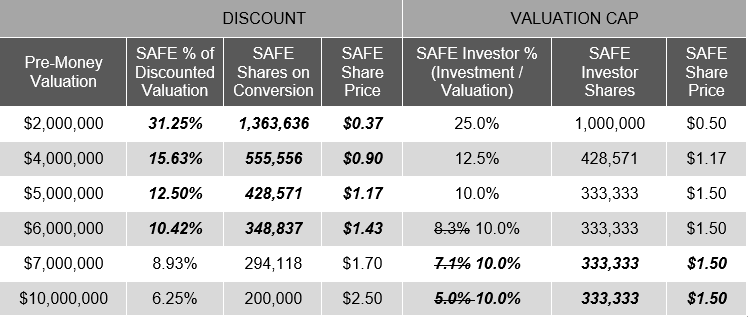

As an example of choosing between a Discount and a Valuation Cap, let’s once again assume we have a SAFE investment of $500,000, a Valuation Cap of $5,000,000 and a Discount of 20%. This method will essentially require us to calculate what the SAFE investor would receive in each scenario, and whichever results in the greatest benefit (i.e. the greatest number of shares) is the method ultimately used. The table below runs through several different scenarios:

SAFE Investment: $500,000

Discount Rate: 80% (20% discount)

Valuation Cap: $5,000,000

Shares Outstanding (prior to SAFE conversion): 3,000,000

Equity Investment Amount: $2,000,000

The above table illustrates the comparison between using the Valuation Cap and the Discount at various pre-money valuations. As we’ve used the same numbers as in prior tables, this skips some of the intermediary steps so that we can focus directly on the comparison on an apples-to-apples basis.

As becomes evident, where the pre-money value is lower, the Discount is preferable, but as it rises there is an inflection point at which the Valuation Cap kicks in and becomes more preferable. It’s important to recognize that this inflection point is not at the Valuation Cap, but is actually at a greater value. This occurs because when we have both a Valuation Cap and a Discount, we’re not comparing the Valuation Cap to the valuation agreed to by the equity investor, but rather to the Discounted valuation determined above.

In the example, a pre-money valuation of $6,000,000 has a Discounted valuation of $4,800,000, which is still below the Valuation Cap of $5,000,000.

Conclusion

All in all, a SAFE can be a wonderfully simple tool to use when raising early stage funding. The key, for both founders and investors, is to understand what it is that you’re using, and to get good advice while using it. As the examples in this article demonstrate, there are some complexities to the “simple” agreement that can be worked through, but usually require some forethought. Without giving adequate consideration to these issues up-front, you may suddenly find yourself converting multiple SAFEs which each have different terms, right near the inflection point between using a Discount and a Valuation Cap, with no clear path forward, which is the antithesis of the goal of using a SAFE. Please also see our companion FAQ Article for further commentary on SAFEs in practice.

[1] This article was originally published July 30, 2020